Principles

Posture Release Imagery rests on the notion that something significant, though not necessarily conscious, comes to us from our distant past.

Can it be that we maintain our continuity and control our support against the force of gravity in the same way as do all land-bound creatures (terrestrial tetrapods)?

Could the relationship of the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the body be key to appropriate support or posture of all these creatures?

Are there common principles in movement control and movement execution that all creatures have… and we frequently manage to ignore?

With PRI experience, the answer to these questions and others seems to be YES!

The Dorsal-Ventral Relationship

The dorsal-ventral relationship to gravity

Healthy and efficient support of our structure comes from the appropriate relationship of our dorsal and ventral surfaces. The entire dorsal surface gently expands upward and outward and the entire ventral surface gently contracts downward and inward in response to gravity.

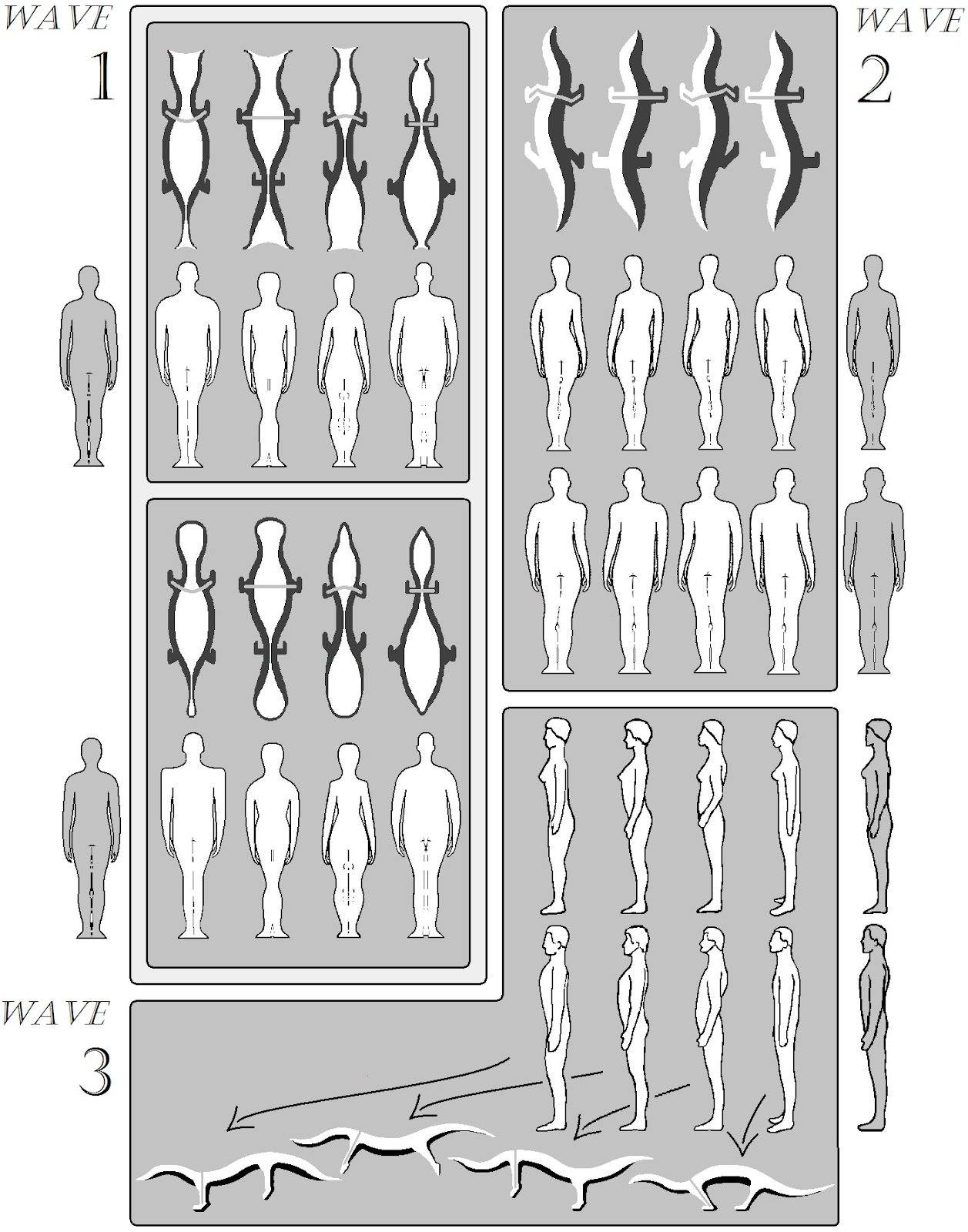

The archetypal creature on the left demonstrates a healthy relationship to gravity and the creature on the right does not. The one on the right side shows the reverse, a more contracted dorsal and more expanded ventral surface.

The dorsal-ventral relationship to the self

The dorsal surface should generally be felt as expanding in relation to a ventral surface that is sensed as contracting… even without respect to gravity.

The dorsal-ventral relationship to dense surfaces

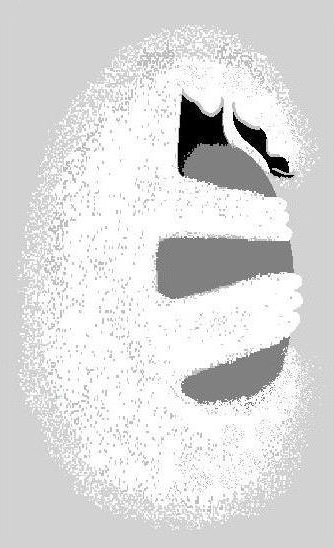

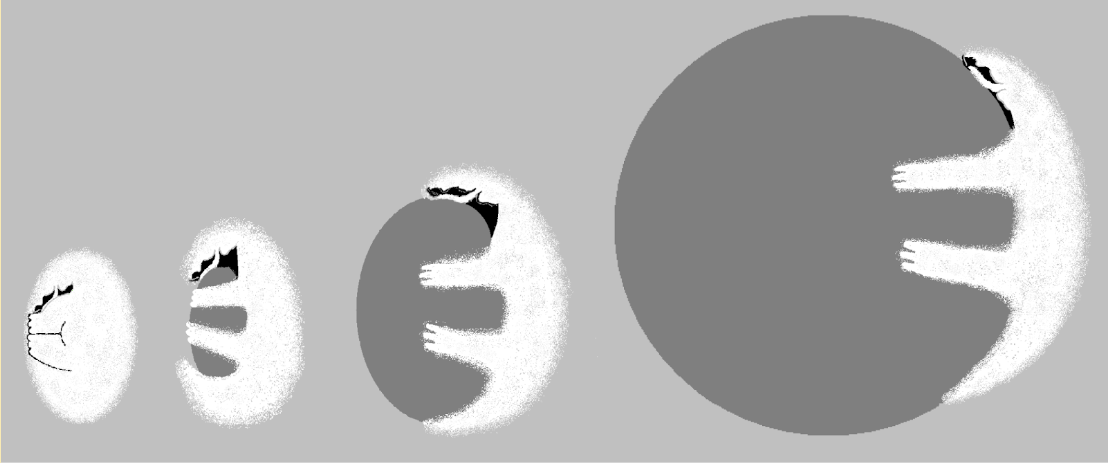

The ventral surface is made healthier not only by perceiving or imagining it in total contact with the earth, but also when it is perceived to be embracing, be fully in contact with, and be supported by a dense surface, independent of the earth.

The dorsal-ventral relationship to "caring" (Other)

The sense of embracing, being in full contact, and/or being supported by a dense surface should also feel like the act of “caring.” “Caring” about an increasingly larger dense surface (as shown) can be thought of as parallel to the caring for the self (1), child(2), family (3), and then larger community (4). As the size of the surface (or the object of one’s caring) increases, the challenge to maintain an imagined full dorsal surface with full ventral contact increases… as it does in “real life.”

The dorsal-ventral "seam"

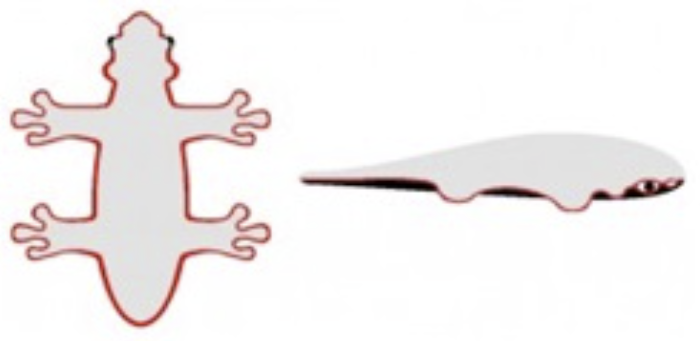

The border area between the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the body is of prime importance in both perception and locomotion. (This borderline is shown here in red on simple archetypal four-legged creatures but is illustrated on human-like figures elsewhere.) Most perception and movement originates along this border or “seam.” Subtle and graceful expression and movement responses begin here. When some tension or increased tone is necessary in the body, as when doing work, it is healthiest when the tension is felt to be closer to these border areas (as well as to the ventral surface) than when in the core of the body. Imagery of changes along this zone is very useful to attaining greater grace in movement and expression, as well as to improving perception of the world outside.

Healthy Divisions of the Body

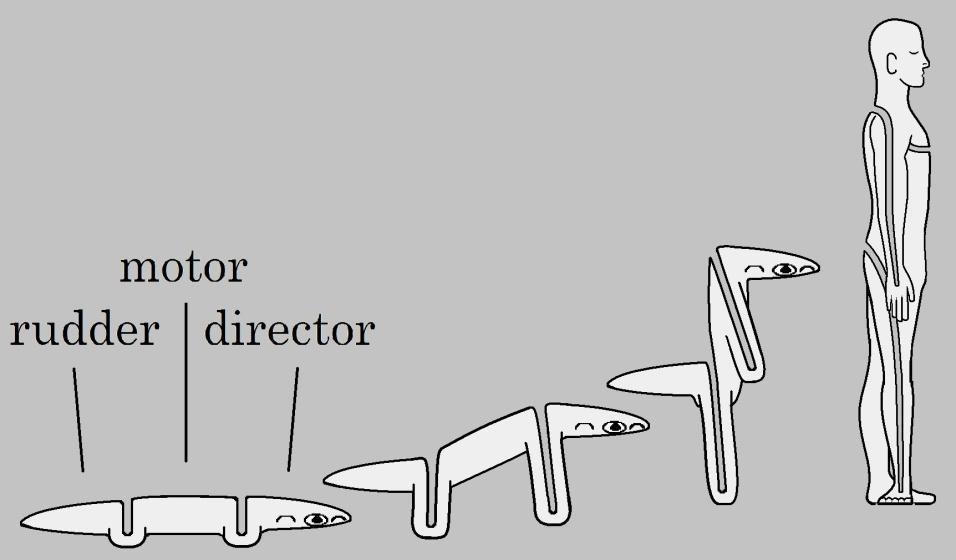

the director, motor, and rudder

The body consists of functional (though invisible) segments that can be viewed (through imagery) as somewhat independent from each other… in order to promote optimal postural health. The locations where the segments are separated can be usefully thought of as balance “pivot points” and “borders” between functions.

There are three basic functional parts of the body that most determine posture and movement. I have simply named them the “director,” “motor,” and “rudder” segments. These segments have distinct functions in support and movement. All three segments in the horizontal creature are obviously horizontal, but only the middle “motor” segment is vertical or “upright” in the third and fourth upright examples. Imagining sharp distinctions between the segments and their orientation is another tool for attaining healthy structure. Experiences of more graceful posture and movement, as well, are attained when these segments are felt and imagined to be substantially free of each other in order to carry out their separate functions.

Posture, Locomotion, and Emotion

There is a meaningful and historical connection between posture, elemental locomotion, and elemental emotion. (This assertion is made by others as well. However, included in this book are some illustrations that begin to suggest how more precisely it is true.)

The evolutionary waves in graceful movement

Early organisms’ methods of locomotion (whole-body peristalsis, lateral undulation, and dorsal-ventral undulation) became the model for neurologically directing graceful and efficient movement of appendages (limbs or wings, for example) in higher life forms. (This idea is not new, perhaps, but its implications can be more valuable to our health and use than is generally understood.) It is more valuable to think of easy or graceful movement as being the consequence of body surface flow rather than just the sense of muscle contraction and release.

The double or repeating waves

Muscle tonus patterns in the head, neck, and front portion of the shoulder and arms are, in undisturbed function, repeated in the rest of the body. This assertion is made toward the bottom of my list but may be the most important. It suggests that the tonal patterns of the face, head, neck, and the front portion of the shoulder and arms (light gray area on the archetypal creatures illustrated here) repeat themselves below, in all the wave forms, through the remainder of the body (dark gray area).

Frozen waves that describe postural and personality types

Evolutionarily early methods of locomotion (whole-body peristalsis, lateral undulation, and dorsal-ventral undulation), when frozen in four phases (or plateaus) of each form of wave pattern, make up a typology of tendencies in posture, movement, emotion, and gender. The postural types coincide with a theory of personality types.